Roughly 10,000 people attempt a summit of Mount Rainier each year and about half succeed. I had it in my head I would summit no matter what. I didn’t know anything about climbing but took the challenge as one to my manhood, another thing I knew little about. That morning in August 1999 I did make it to the top but barely, sobbing and broken, one of my gloves blown off and all my water spilled in my pack.

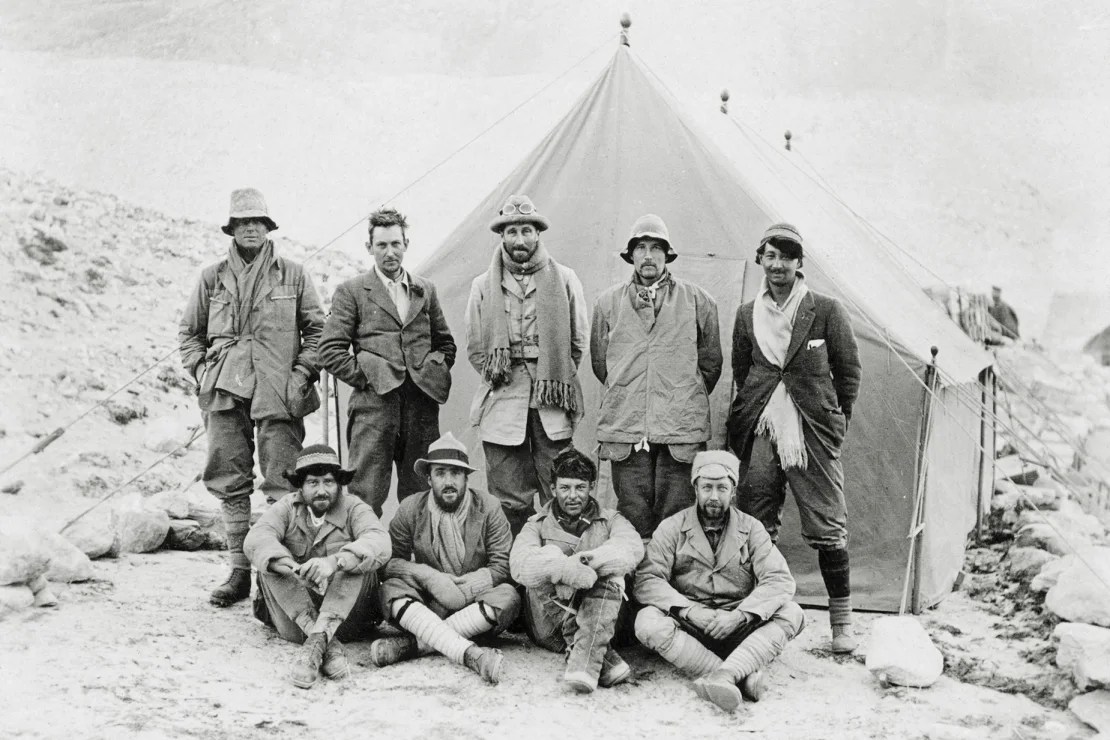

We didn’t get the guide we’d hoped for and instead, a young climber named JR agreed to do it as a favor for the more senior guide. JR had a solid climbing résumé and was training for an Everest expedition to recover the climber George Mallory’s personal effects. Mallory had led a 1924 summit attempt, the first known party to attempt Everest, but gone missing two thousand feet below the top, around 26,000 feet elevation (660 meters). JR was proud to be part of the mission to recover Mallory’s eyeglasses and other artifacts, such as a camera that could include evidence as to whether they’d actually summited.

About a dozen of us had trained to climb Rainer, gotten jackets with our names printed on them, and raised $10,000 for cancer research. We were an even split of men and women with me the youngest at 28, and Dave Olsen, one of the original founders of Starbucks, the oldest (in his 50s).

I try to imagine what it was like for JR to take in the sight of us at the parking lot when we first met, a day before our summit attempt. It must have become real to him at that moment, even though he knew what he was signing up for. JR only had one other climber with him he could trust, a friend named Kent, and 12 others whose lives he was now responsible for.

Many who climb Rainier start on the Paradise side and climb 5,000 feet (1,500 meters) to Camp Muir, named after the Scottish-American naturalist John Muir, who’d climbed Rainier in 1888 and chosen this spot to camp. Muir observed pumice on the ground there, suggesting less wind, and built a rock wall to protect the climbing party from the winds.

Climbing to Muir at 10,188 feet (3,105 meters) with all your gear, in snow boots, is a humbling feat. JR used it as a way to suss out our fitness levels and I barely passed. I’d carried a microcassette recorder with me and recorded the sound of us marching out of the paved lot onto the snow because I loved the crunching sound our boots made and the metallic jangling of our crampons and ice axes on our packs. I also recorded the meeting we had at Camp Muir with JR the night before our summit, once we’d finished melting snow for drinking water and gotten our tents staked down.

Okay: what we’re going to need to do tonight to prepare for tomorrow’s climb. First, if you get up tomorrow and for some reason don’t feel like climbing, don’t leave Camp Muir. Since this is a charity-climb thing, we don’t have the luxury to just send people back down. We’re counting on you to make the right decisions; we’re counting on you to self-arrest. You know, if someone decides they can’t make it, I don’t know. I don’t really know what we’ll do. I guess we could turn a rope team, but we’re not going to know until it happens.

Things that you’ll need tomorrow: you’ll want to bring every stitch of warm clothing you brought to Camp Muir. Five layers on top, three layers on the bottom. Two quarts of water, at least. Food. Sunscreen. You’ll want to keep your sunscreen on you, in a pocket, or it’ll freeze. Glacier goggles: don’t forget your glacier goggles while you’re packing, in the dark. Headlamp and extra battery. Keep your extra battery in your pocket, you’ll want to keep it warm. Camera and film, ice axe.

What you won’t need tomorrow: sleeping bags. If things go bad tomorrow we won’t be staying out overnight on the mountain. We won’t bivouac. Does anybody know what bivouac means? Bivouac is the French word for mistake. We won’t be doing a bivouac.

You know, we’re going to go as far as we can until we reach a point where I’m saying to myself, I don’t feel like I can control this situation anymore. And usually by the time we reach that point you’re saying to yourself man, I wish he would turn back. So don’t bring your sleeping bags. I’ll probably have a few people bring one though, just in case.

Alright. You won’t need your ski poles. You won’t need your wet cotton T-shirt and socks from today. We’ll hang those in the tents tonight and tomorrow when we come back down they’ll be dry for the climb back down to Paradise.

What you’ll need to survive on Mount Rainier tomorrow: water. Food. Your ice axe. Your brain. Again, since this is a charity climb, we’re expecting you to make the right decisions and to think up there. You can’t just go on autopilot. If you see a rock, yell “rock.” Look for it, spot it with your headlamp, and get out of the way at the last minute.

I looked around at the others, huddled together on the snow, and we all looked scared shitless. JR went on to describe the route, which started at Disappointment Cleaver, the most dangerous part of the climb. Because of the potential for loose, falling rock, we had to move through it fast without stopping. It would take two hours until we got above it, to Ingraham Flats. JR compared “the DC” to walking through the chamber of a gun: every hour it clicks and every couple weeks there’s a bullet, and if you get hit by the bullet, you’re toast.

We got lucky that day I guess, because most of us made it to the top and the few who didn’t just had to wait a few hours tucked in sleeping bags and staked to the side of the mountain, down lower.

In the account I wrote is the start of a writing style I’d develop over the next 25 years. There is something endearing and humbling seeing the first glimpse of that young writer’s voice, marveling over how I managed to do such a difficult thing, how far I’ve come, and how far I’ve still got to go.

“took the challenge as one to my manhood, another thing I knew little about.” classic line. Are you saying the essay above is what you wrote 25 years ago?

LikeLiked by 2 people

Hi Jeff, thanks for this! I only included the quote from the guide from that original essay. I have the microcassettes which I’d intended to play back and transcribe but my player is broken and they now cost like $200 for one (ha!). Fortunately I had some of the transcript from the guide in the original essay I was able to use.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This got my heart rate up.

The image of those poor sods pinned to the mountainside in sleeping bags has banksied itself into my brain. The picture of you has been chiselled in too: Rugged man. (I wish I could italicise that ‘man’ in WP).

What a climb and what a great recapitulation, Bill.

Be well and do good.

DD

PS. I better leave my brain to science, what with its valuable load of chiselled in images. That would be ok with you, Bill, wouldn’t it?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes leave the brain to science ha ha! Glad you enjoyed this David, thank you. Has been fun reengaging here mostly because of good folk like you I miss. Back soon! Appreciate you reading and your always thoughtful and uplifting words.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Love the B&W photo. A not to another age!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hey thanks Bruce! Looking forward to catching up today!

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s quite the story. Sounds like your manhood learned a little about itself that day, and the lesson stuck.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Dave and thanks for reading! Hope you enjoyed that storm we got last night; I assume you got the same one we did if you were down in Portland area this weekend.

LikeLiked by 1 person